One month ago, my father, Irving Teitelbaum, passed away. He was 93 years old and had a good, long life, but his passing is still a big loss. I learned a lot from him and believe that these lessons can also apply to First Gen College.

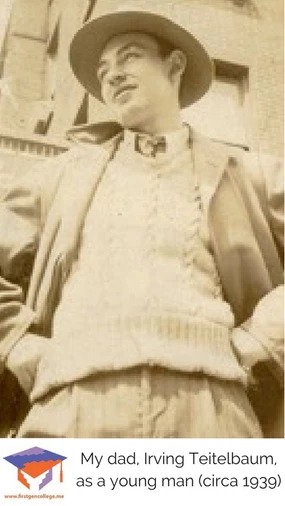

My father was the youngest child of two Jewish immigrants from Austria Hungary who came to the US at the turn of the 20th century. His parents worked in the garment industry, making ties and doing other piece work in the Lower East Side of New York.

Though they didn’t have much formal education, my grandparents felt very strongly about the value of education. To them, education was a Jewish value; the purpose of learning was to pursue more knowledge, to engage with big ideas, not simply a pathway to greater economic opportunity.

My father was a first generation college student and was thrilled to have the opportunities for education available to him. He loved to learn, and he had a broad and voracious appetite for study. As a young man, he was ordained as an Orthodox rabbi to please his mother, though he never practiced. He got a doctorate in Egyptology and Assyriology, which meant that when I was a kid, when we went to the Brooklyn Museum, he could read the hieroglyphics. He also earned a master’s degree in psychology, and he was a school psychologist in New York City public schools for most of his career.

He was a bit of a Renaissance man and a genuine amateur- someone who pursues study or activities for passion and pleasure, rather than pay or prestige. As proof, he would have explained that the French root of amateur- ama– means love. To my father, the public library was like a candy store. He read upwards of a dozen languages. In addition to vast Jewish scholarship, he was interested in reading classic texts in the original- from the New Testament in Greek to Dostoevsky in Russian. He read newspapers in Chinese and Japanese, Turkish, Arabic, and more. All of it was done slowly, with a dictionary at his side, but he persisted.

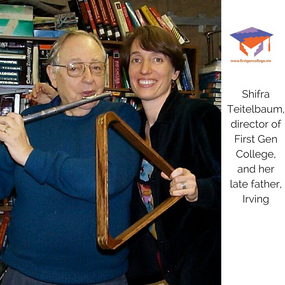

The same was true of his love of playing music. He didn’t have great talent, but he played almost every instrument you could imagine. His mother insisted he learn to play violin as a boy. He left it behind once he had a choice, only to return to it in midlife. But as an adult he played piano, trumpet, clarinet, saxophone, accordion, viola, trombone, flute, guitar, harmonica, and more. He didn’t have a great ear or much rhythm, but he got so much pleasure out of it.

Throughout his life, he was always taking lessons on multiple instruments. Until the last year or so of his life, though he no longer practiced between lessons, a teacher came to the house each week to play piano and trumpet with him.

Times were different when my father was growing up, and despite being from humble beginnings, he had privileges that enabled him to pursue his passions while carving out a career that, along with my mother’s work as a teacher, supported a middle class family.

Today, college tuition and student debt have skyrocketed. Given overcrowding and other challenges at community colleges and state universities, it can take years and years to complete a degree.

First gen college students from low income communities of color experience racism and other structural barriers. They don’t know many well-positioned people in higher ed and careers who they can ask for advice or to open doors. Many first gen college students of color in today’s schools face barriers my dad couldn’t have imagined.

And yet, in his honor and his memory, and because of the beauty and the purity of the idea, I still think it is important to cherish the gift of curiosity, and to recognize and nurture our passion for learning. School standardization and high stakes testing can sometimes interrupt that natural curiosity. And the challenges of paying back student debt can sometimes make choosing majors and careers become strategic financial decisions rather than ones driven by personal passion.

Yet there is so much more that learning can provide- for personal satisfaction and growth, for intellectual stimulation, and for more responsible and informed civic involvement.

Whatever practical decisions first gen college students need to make to survive and succeed, I hope we can each still connect with and nurture our inner curiosity, our natural interests and personal passions. And I hope we can commit to tend it, whether as our primary focus or for personal pursuit.

It certainly offered my dad a engaging and satisfying life, and has been an important model for me in my life. Pursing my innate curiosity and interests have enriched my life in so many meaningful and inspiring ways.

Thanks, Dad. I love you.